Microbes

04 Apr 2018

- Types of Microbes

- Smell

- Digestion

- Gut-brain axis

- (Lack of) Microbial Diversity in Developed World

- Sidenotes

- Conclusion

I recently read “I contain multitudes” book. It turned out to be much better than my expectations - and I generally have high expectations from the books I read.

Let’s take a huge step back before we jump in - an organism can be either a Eukaryote (animals, people, amoeba etc) or a Prokaryote. Eukaryotes are very diverse - it includes mammals, plants, and many single-celled organisms. On the other hand, Prokaryotes consist of Bacteria and Archaea. Most of us have grown up fearing bacterial diseases. However, our relationship with bacteria turns out to be far more complicated and interesting. While many bacterial diseases are fatal in nature, we also depend on many bacterial species to get us through the day.

For the purpose of this post, I will use Bacteria and Microbes interchangeably.

I contain trillions of bacterial lives in my body. When I make the trip from my home to the office every morning - those trillions of microbes also make their trips by virtue of staying on the “Hardik” vehicle. Similarly, when I hike up Torres Del Paine, microbes are also hiking with me. You get the idea - since these microbes are a constant part of our lives, it’s best not to think of them separately. We can understand this dynamic better if we look at the host (us humans) and our microbes together, instead of looking at them separately.

Of course, the microbial population is changing all the time. If I were to maintain a daily log of the bacterial strains in my gut, I would be able to spot differences over time (This post describes the change in the mouth microbe populations). Changes in diet, environment, and location can significantly affect the microbial mix. Antibiotic medicines also cause significant changes - however, those often tend to be temporal changes and microbe population usually recovers soon.

Types of Microbes

I like to think of the human body as a cylinder. In other words, the human body has a hole passing through it. Entire surface of this cylindrical body has microbes on it. The skin is covered with various microbial strains like Propionibacterium, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus. Our mouth is covered with Streptococcus bacteria. And our gut, the inner surface of our cylindrical body, contains Bacteroides.

How do these microbes get in our guts in the first place? This is an interesting question since a newborn baby is sterile at birth - it does not contain any microbes at all. Turns out we’re selective in the type of microbes we allow. Our microbial population goes through multiple stages as the baby ages. Baby develops the initial important gut bacteria Bifidobacterium with the help of mother’s milk. As the baby’s diet changes, milk-digesting specialists like Bifidobacterium give way to carbohydrate-eaters like Bacteroides. Microbial ecosystem reaches their adult stage between the age of 1 to 3.

The microbes are helpful only outside of the human body. If they get into the body, they can cause sepsis. Our body works hard to make sure they stay outside. Our gut, the inner surface of the cylinder, has 3 primary defense mechanisms:

- Mucus: We use mucus to cover tissues that are exposed to the outside world: guts, lungs, noses, and genitals. Mucus is made from giant molecules called mucins, each consisting of a central protein backbone with thousands of sugar molecules branching off it. This dense mucus wall stops wayward microbes from penetrating deeper into the body. Additionally, bacteriophages or phages, are attached to the mucus - they help kill the microbes.

- Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs)

- Antibodies

The gastric acid also helps destroy many microbes.

Smell

An average human has almost 15-20 sq ft of skin. Different areas of our skin harbor different types of microbes. Humid and warm armpit have different microbes than those found on the palm. Smell is one of the traits where microbes play a crucial role.

As mentioned above, the bacterial strains found on our skin mostly fall into the following genera (categories):

- Staphylococcus

- Corynebacterium: It converts sweat into something that smells like onions, and testosterone into something that smells either like vanilla, urine, or nothing, depending on the sniffer’s genes.

- Propionibacterium

Smelly armpits are often correlated with the prevalence of Corynebacterium strains - link.

Digestion

Most of our gut bacteria fall are of the Bacteroides genus. Unlike the aerobic skin microbes, gut microbes are anaerobic. In other words, our gut microbes do not have access to Oxygen.

Humans don’t have all the required genes to digest our typical meals. Therefore, we rely on our microbes to help us break down some food components.

Microbial population is well suited for this task. Unlike humans, microbial ecology can evolve very rapidly under the right conditions. Humans evolve by passing down mutations to children - it’s called vertical gene transfer (VGT). This is slow. It may take a few generations to evolve a useful mutation required for digestion. On the other hand, bacteria rely on the horizontal gene transfer (HGT), sometimes called lateral gene transfer (LGT). They can pick up random DNA strains from their environment and incorporate those genes into their body. This makes them extremely versatile digestion machines.

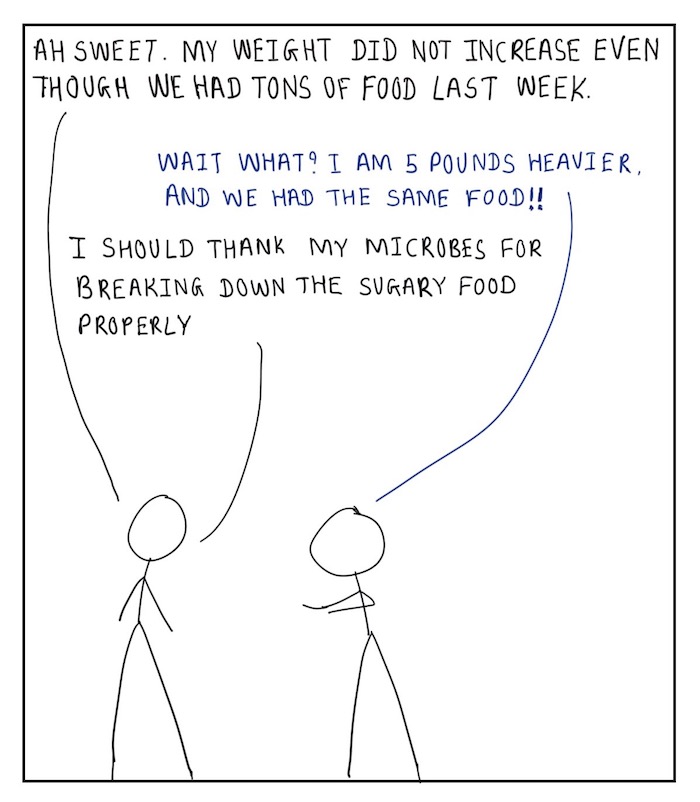

Obese individuals have different microbiome communities than the lean individuals. There is a correlation between the obesity and the microbiome strains. However, the causation is not entirely clear to me in this case.

Gut-brain axis

Psychiatric problems and digestive problems often go hand in hand. Biologists speak of a “gut-brain axis” - a two-way line of communication between the gut and the brain.

Studies have shown that any kind of stress - starvation, sleeplessness, being separated from one’s mother, the sudden arrival of an aggressive individual, uncomfortable temperatures, overcrowding, even loud noises - can change a mouse’s gut microbiome. The opposite is also true: the microbiome can affect a host’s behavior, including its social attitudes and its ability to deal with stress.

Some bacterial strains are shown to increase the effect of GABA neurotransmitter. GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter - most neurotransmitters (e.g. Glutamate) are excitatory in nature. GABA enhancing drugs are often used to treat anxiety and depression. In other words, some studies on rat models suggest that certain microbial strains can behave like a milder form of an anti-anxiety antidepression medicine.

A recent survey paper suggests probiotics might help improve psychiatric disorder-related behaviors including anxiety, depression, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), obsessive-compulsive disorder, and memory abilities, including spatial and non-spatial memory. Most of the experiments had used either Bifidobacterium (B. longum, B. breve, and B. infantis) or Lactobacillus (L. helveticus, and L. rhamnosus).

Gut-brain-skin axis

“Gut-brain-skin” is an emerging theory suggesting that the gut microbes can affect the skin homeostasis, skin inflammation, hair growth and peripheral tissue responses.

(Lack of) Microbial Diversity in Developed World

Diversity of the microbial population is decreasing in the developed world. That brings its own set of problems. The increase in the autoimmune disease diagnosis is often attributed to the shrinking diversity.

Sidenotes

- These medium posts of a microbiome enthusiast are interesting.

- You can actually buy bifidobacterium longum strains from a pharmacy.

- You can use services like ubiome or viome to get a profile of your microbes. I have not used them and I don’t plan to use them in near future - because I feel there is a lack of actionable data at the moment.

- qiime2 is a microbiome bioinformatics package.

Conclusion

While researchers have found several correlations between microbial populations and health parameters, we don’t know the causation at the moment. It’s not entirely clear how microbes and humans (or animals more generally) are affecting one another. I am hoping we will have a better idea in the next 5-10 years or so.

PS: I have disabled the comment section. If you have a comment, please feel free to email me at hardikp12@gmail.com or reach out to me on Twitter.